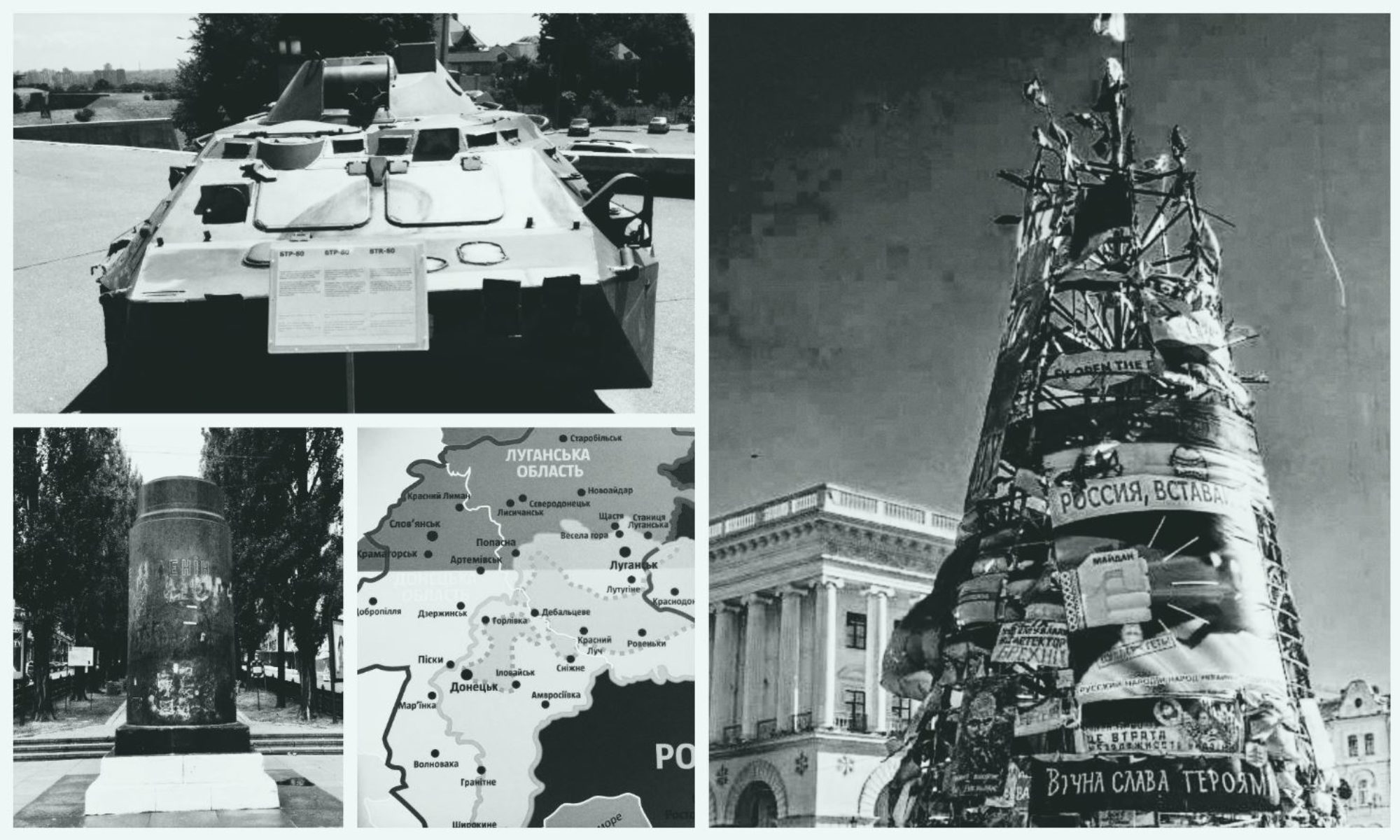

The war in the Ukrainian Donbas has entered its fifth year. Though the military clashes are less intense than in 2014-15, casualty levels, including fatalities, remain high. Despite two armistices, conducted under the name ‘Minsk Protocols’ in September 2014 and February 2015, the various sides are far from a permanent settlement. A sizeable portion of Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk regions, including the two major cities, remain under occupation by rebels, backed materially and, at key moments, militarily by the Russian Federation.

Our conference will examine Russia’s policy in this region, as well as the events that precipitated the uprising in the Donbas: the Maidan protests of November 2013 to spring 2014 in Ukraine and their impact on the far eastern areas. Our premise is that there is ample evidence the prevailing Western media line, attributing the entire conflict to Russian machinations or imperialism, is simplistic and inaccurate. The Donbas region has a lengthy history of autonomism and individuality dating back to industrialization of the 19th century as well as the Soviet period. Disaffection for Maidan was deep-rooted and far from illogical. These anti-Kyiv sentiments encompass far more than preference for the Russian language and pro-Russian feeling.

In turn, we will examine the possible future options for this region beyond a ‘frozen conflict’, keeping in view Canada’s commitment to Ukraine, its introduction of military missions to the western part of the country, and support for the development and training of the Ukrainian army. What sorts of solutions would be acceptable to Canada, and how far should we be committed to the goals of the current government of Ukraine? Could Canada play a role if a UN peacekeeping force is introduced on the Ukrainian-Russian border, as some sources have advocated (Vladimir Putin, for example, is sympathetic to this idea)?

Ultimately, our project considers the Donbas region an integral part of Ukraine that needs to be better integrated into mainstream thinking. The area has been subject to much over the past eight years: oligarch ascendancy; control over much of Ukraine’s policymaking in 2010-14 through its ruling Regions Party and its president Viktor Yanukovych; followed by brutality and destruction through a costly war in 2014-18. The war has resulted in over 11,000 deaths and the uprooting of an estimated 1.5 million people from the industrial heartland of Ukraine. Resolution of this conflict would bring an end to the most destructive war in Europe since the collapse of Yugoslavia. But how could it be achieved?